1. The importance of training both Qi and Body

In exercise and fitness, training the body usually starts with physical movement. At first, it’s muscle-driven, but muscle-based effort alone quickly leads to fatigue and wear. Inevitably, qi (vital energy) enters the process, unfortunately it’s not as the driving force, It’s like a car engine: it begins with the mechanical movement of pistons, but soon relies on the force generated by the expansion of gas combustion. Real strength doesn’t come from isolated muscles, but from whether the whole body can coordinate its muscle groups to generate power focusing at the single point.

Think of ordinary glass compared with a convex lens: the latter can focus sunlight until it burns. Or think of a baby: when a baby grabs something, the grip feels astonishingly strong. That’s because the baby instinctively recruits the entire body’s muscles. The key to this lies in breathing. Laozi once asked: can you breathe like an infant?

This is especially emphasized in the internal schools of martial arts. A deep breath engages the maximum number of muscles, forming unified strength. Through qigong and meditation, one can train the breath to sink into the dantian and even down to the soles, until it becomes second nature. This method is not just for martial arts or exercise—it can also help refine posture in standing, sitting, and everyday movement.

2. Why choose Taiji and the Shakuhachi

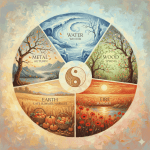

I choose Taiji because it is rooted in the same philosophical foundations as Yin–Yang, the Five Elements, and the meridian system in Chinese medicine. It heightens one’s awareness of the body. As practitioners learn to naturally synchronize movement with breath, relaxation gradually becomes instinctive.

I choose the shakuhachi, the Japanese bamboo flute, because it mirrors and amplifies the quality of one’s breath and physical state. Breath practice in itself has no fixed standard, yet shakuhachi playing introduces one: it allows the breath to be measured in terms of length, steadiness, smoothness, and softness, while linking it to physical ease and relaxation. In this sense, art provides a benchmark for breath, and shakuhachi practice becomes another expression of Eastern music: one enters Dao first, then Zen—another way to understand music.

3. Method

We begin with Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, using them as the guiding thread throughout practice. Some movements are adapted to suit small spaces. At first, effort relies on clumsy muscular strength; later, it transforms into the subtle power of qi.

4. In the end

When you can play a high note without tension, or train as if an opponent were there even when none is present—and respond as if none existed when one does—you cultivate an unwavering calm.

In this way, composure becomes constant. From qi to posture to mindset, good fortune arises naturally. In Chinese, the words for “luck” and “the circulation of qi” share the same term: yunqi.